Who Stole My Country?

The last thing the world needs is another blog. I’m already overwhelmed by the amount of information I process every day. And yet, here I am, adding to the clutter with another blog

Introduction

When did you stop believing that government can be trusted? When I was young (1935 to 1948) we believed that government represented us, ordinary people. Government programs had brought us through the great depression, won World War II, established free state universities, linked us together on super highways, set up a retirement program for everyone and encouraged the largest expansion of a comfortable “middle class” perhaps in history.

Today, 87% of Americans do not trust their own government nor mainstream media.

Not only that. Belief in the American dream has plummeted since the 1930s and ‘40s. There are no completely trustworthy statistics for attitudes toward government during that time. Polls largely ignored women and focused on the affluent, for example. But according Pew Research, “… despite their far more dire economic straits, they remained more optimistic than today’s public.”[i]

“Large majorities favored the federal government providing free medical care for those unable to pay (76%), helping state and local governments cover the costs of medical care for mothers at childbirth (74%), spending $25 million (big bucks in those days) to control venereal diseases (68%), and giving loans on “a long time and easy basis” to enable tenant farmers to buy the farms they then rented (73%).”

Moreover, a 46%-plurality favored concentration of power in the federal, rather than state government (34% favored the latter),” according to Pew.[ii]

Today that optimism has been almost completely reversed! This blog will explore how Americans turned against their own government over course of my lifetime. It will be a personal recollection of how we got from there to here. I was given an incredible vantage point from which to view these wrenching times as a journalist with a progressive radio network, Pacifica, during the sixties, a hippie drop out and manual laborer in the Seventies, and a documentary producer covering stories around the world ever since.

What happened between 1935 and today? When did you stop believing in the beneficent effects of government?

Or were those good times just a passing illusion, an expression of FDR’s genius and compassion, as ephemeral as any human life?

[i] Pew Research Center Fall 14, 2010 How a Different America Responded to the Great Depression. BY TOM ROSENTIEL by Jodie T. Allen, Senior Editor, Pew Research Center

[ii] (http://www.pewresearch.org/2010/12/14/how-a-different-america-responded-to-the-great-depression/)

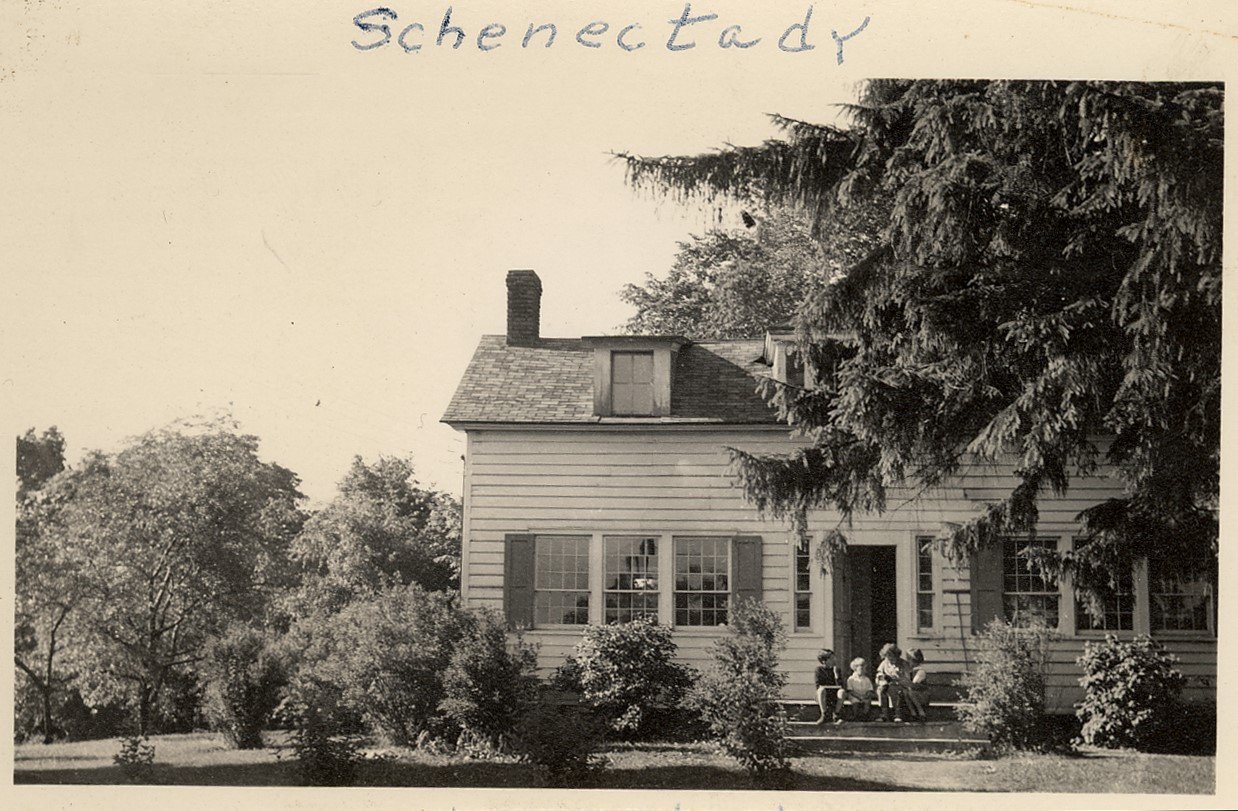

My childhood was totally different from the childhood of my children. I had more in common with children from the 18th Century than with children of the 21st Century.

Building immunities

We lived on a country road with farm family raising chickens, pigs and cows on one side, a retired couple on the other and an apple orchard across the road. We had one car, which my father drove to work. My mother stayed home. She didn’t really have to leave the house much, because most essentials came to her. Dairy trucks brought eggs, butter and milk, although we got ours next door. Knife sharpeners and pot menders and vegetable truck farmers drove by once a week. Door to door salesmen peddled a wide range of household goods. Doctors made house calls. There were no after school sports, shopping sprees at the mall, voice or drama lessons, nor any of the activities that occupy today’s children of the American middle class. At least not for country boys.

Nobody I knew had much in the way of material possessions. A week’s trash fit in one, small can.

My mother was a health nut. She kept my bedroom window open summer and winter, even if it was only a small crack during snowstorms. Antibiotics had not yet been invented and childhood illnesses from chicken pox and measles to common colds and runny noses, sent me to bed with high fevers and much misery, but my survival left me with a strong physical constitution as an adult.

Our diet included Cod liver oil, chicken livers and real butter. We rarely used the new butter substitute, margarine, that came in during the war. It was a white Crisco like substances with a packet of yellow die in one corner. I loved to kneed the yellow coloring into the white saturated oil, but it tasted awful. We always ate a full breakfast with orange juice or grapefruit. My mother would cut between each separate grapefruit wedge and carefully separate the fruit from its surrounding tissue with a knife. Sandwiches for lunch. Peanut and jelly. Cheese and lettuce. Tuna fish salad. In the evening, a full sit down dinner with desert. I loved the rhubarb pie made from rhubarb that grew wild outside our cellar door.

We had to find our own amusements. The dirt cellar under the house had a hidden room behind a shelf designed for home canned fruit and vegetables. We put up a lot of canned goods every summer. The shelf was heavy with them. But there was a section in the center that could be pulled out and a small stoop space lay behind them, a stop on the Underground Railroad for runaway slaves, we were told. A great hiding place for rainy afternoons.

My mother believed that playing outside built character and endurance. She started pushing me out when I was a toddler, dressed for inclement weather in boots and rubberized pants with a coat and hat when it was raining or galoshes and a snow-suite in winter. I stayed near the front porch or with my brother or sister, the front yard, the corner garden, but as I grew older I ranged further and explored the unknown until it was familiar. The back yard sloped down to a creek ten feet below in a steep ravine, a place to dam up water and chase tadpoles. An old barn with a decrepit loft, off limits of course, was a favorite. The apple orchard across the road.

When I got a bicycle at eight my world quickly expanded. Rosendale Road and the dirt lanes off it led to open fields, woods and sand dunes, a smelly bog with pussy willows and huge frogs, railroad tracks with freight trains that beckoned to unknown places and crushed pennies flat on the tracks.

It was a life with no adult supervision when I was away from home, hours at a time. I learned to fall back on my own resources when I was hurt or bored. I learned to avoid the hobos, talk my way out of being trapped in a culvert. I didn’t have many playmates. My best friends were the children of a hardscrabble family about a mile down the road, just past the Grange.

The afternoon Kathy pulled up her dress to show me how girls were different from boys is still riveted in my mind. She was standing in front of a wood burning stove, bathed in light streaming through the broken screen door, barefoot on curling linoleum speckled with chicken poop. The two kids were about my age. Randy wore blue overalls without a shirt in the summer and Kathy wore a cotton, polka dot dress with nothing underneath. We all became best friends.

We played hard, cowboys and Indians or Nazis and resistance fighters. Randy and Kathy were happy to be cowboys and Nazis. They had so little chance of being authorities, I suppose. It was my job to outmaneuver, out run, and out fight them to achieve some goal. One game sent me home with my first serious concussion and a bloody nose.

My family would take walks in the woods as soon as spring arrived after the long up-state winter. A week before the first crocuses poked through the dormant garden beds, before tiny Witch Hazel flowers appeared in the woods, skunk cabbage bloomed along the creek bed behind the house and in moist bogs in the woods, the real harbinger of spring. This native of the Northeast and Midwest is one of my most vivid memories of Schenectady. The leaves give off a pungent smell of rotting meat when they are touched. The smell is pretty mild otherwise, but my mother had a nose for it, and on walks in the woods in spring she would suddenly stop, crinkle her nose, sniffing the air and announce with a combination of professed disgust and obvious enthusiasm, "skunk cabbage! Christopher! Be careful!"

In April, the stiff, waxy spikes the color of eggplant, splashed with bright red or mustard yellow poked through the snow. One of its fascinations for a child like me, skunk cabbage, at this stage, was warm to the touch, deep inside some 40 degrees warmer than the air around it, as the plant converted the starch stored in its deep roots to sugar, and that warmth with the smell of rotting meat attracted flies looking for fresh carrion in which to lay their eggs or other pollinators simply looking for a warm place to rest. The flowers faded in a few weeks and huge, green leaves some two feet long and a foot wide emerged. With less caution than my mother appreciated, I stumbled through the skunk cabbage and was even known to plunge my hand into their disturbingly warm interior. By June the leaves were gone, not simply dried and dead, they disappeared entirely for the rest of the summer and fall.

Sunday Drives

Our main family entertainment when I was child was the post war ritual of “Sunday Drives." Other families may have done this into the Fifties, but by then our weekend drives had destinations ... a remote beach, a stand of redwoods or a mountain with a view.

The idea today that any parent would get in a car with children to take a drive with no particular destination in mind, solely for entertainment, seems unthinkable. But in the Post War Forties, with cheap gasoline once more available, from Rosendale Road we would head out in our four-door car, father driving, mother sitting next to him in the front seat, we three children crammed in the back seat. Children today would bitch and moan with boredom despite their music players, game counsels and mobile phones. All we could do was look out the window (fighting was absolutely forbidden) and, when things got really desperate, listen as my mother read to us. Driving home in the dark, stuffed together though we were, I would fall asleep as we all sang camp songs.

We drove on small, two-lane roads, most only recently paved and a few still gravel or graded dirt, through the woods, up hills and down, slowing where the road cut through rocks so my brother, a student geologist, could examine the rocks. "I'm not asking you to stop, just slow down," was his plea and it became a family joke. We went through small towns, not yet tourist attractions, stopping occasionally at tiny general stores for gas, candy or drinks. The stores were small clapboard structures with asphalt shingle roofs. Usually a covered porch with a couple of chairs and a bench, one musty, dark room with shelves of canned and bottled food, bright red cans of kerosene for stoves and lamps, a few hand tools, all illuminated by naked light bulbs hanging from the ceiling and light filtering in through small paned windows, glass streaked with dirt and dust.

A few of the stores would sell post cards, but not much else for tourists traveling through. Mother always packed a lunch basket and we never stopped to eat at restaurants, so the total cost of these excursions was the gas and a few bottled drinks. Whatever drama these drives had was self inflicted, frequently focused on the ambiguity of where to stop for lunch. Dying for a break in the driving and a chance to stretch our legs, we children would plead for the next place we could safely pull off the road, but inevitably either my mother or father would find something wrong with the meadow or stream or wide spot in the road, and after slowing down to scrutinize it we would pass on. Then the recriminations would begin about whose fault it was that we gave up that quite respectable spot as we continued looking for one that was even better.

Jenny Lake

I remember a long drive from Rosendale Road to Jenny Lake, where, during the years we lived in Schenectady, we spent much of each summer. According to a recent Internet search, Jenny Lake is 39 miles away from our home on Rosendale Road and it can be reached in one hour and three minutes.

Could the cars and roads of the Thirties, unimproved during the war years of the Forties, really have made the journey three or four times as long? My brother George said no, it only took an hour, although it took him most of the day to make it on his bicycle.

Our father would drive us up on a Friday afternoon, spend the weekend helping us settle in and then return to the city for the week. Gas rationing didn’t allow for more frequent visits.

We went every summer from 1937 when I was two and my older brother George was eleven and Mimi eight. Our last summer was 1948 when we left Schenectady for good and headed to New Jersey. George was entering Harvard by then and Mimi was in her last year of High School. They were not often at Jenny Lake by then.

There are photographs of the three of us playing together, picking blueberries, eating breakfasts of blueberry pancakes seated at an enamel table in front of a kerosene kitchen stove, but I have no memory of where they slept or what they did during the day.

I remember spending a lot time alone with my mother, leisurely mornings when I would play in the bright sun in a small meadow in front of the cabin, mid-morning walks to the lake where my mother would read while I played in the sand, caught minnows, chased butterflies, camped out and played fort under a rowboat pulled up on shore, or daydreamed in the huge, twisted roots of trees along the lake shore, staring at clouds.

Jenny Lake was just inside Adirondack State Park, and it was higher and more mountainous than the farms around Rosendale Road, with smells of pine needles and open hillsides with low lying blueberries baking in the afternoon sun, instead of the ferns, watercress and skunk cabbage in the woods and fields around my home.

The lake was owned by General Electric, protected by a series of exclusionary laws: no new homes, no camping, no trespassing, no electricity, no city water, no motorboats, no telephones to the outside world. Simple and primitive, the ethic of the old American ruling classes, the cabins were set back from the lake, private and separated from each other, consisting of four small rooms on the ground floor and an attic, which I shared with hornets and bats. “Don’t be silly. They won’t hurt you if you don’t disturb them,” my father told me. My brother teased me about being afraid of them. Believe me, I never went near them.

On the trip from Rosendale Road, I sloughed off the trappings of settled life. I felt my excitement rising when we hit the “wee” road, so named because our father would accelerate over the small hillocks and we’d rise out of seats on the way down the other side, screeching, “wee!” Through Saratoga Springs, with a stop for gasoline. Then we turned off the main highway onto smaller roads, sometimes stopping in the tiny village of Corinth for last minute items. On the final stretch toward the lake, we stopped at a barn cut into the side of a hillside, shaded by huge maple trees. Stacked well back in the cave beyond the barn, separated by layers of sawdust, was a mountain of ice blocks, cut from the lake during the winter with huge crosscut saws and held over in the cave through the summer. The Ice Man would leverage blocks of ice out of the stack with forged tongs and chisel them into manageable pieces.

Without electricity, we kept our perishables in the icebox and made frozen ice cream by hand with salt and chipped ice. I still have a tendency to call our modern refrigerator an ice box, and I still vividly recall the huge blocks of ice slowly melting in the insulated box, chipping off small shards with an ice pick for the rare iced tea on a hot afternoon or ice cream for dinner, and the smell of the chilled, moist musky interior when the ice was almost melted. It must have lasted about a week, because Pa always brought up a few new blocks in a cardboard box when he arrived on Friday afternoons.

We shared a small sandy beach and dock with a few other cabins, all owned by GE. The dock went out into ten-foot deep water. Apparently, from the age of two, which I believe was our first summer there, I would run to the end of the dock and jump into the water hoping for the best ... either that I would miraculously learn to swim or that someone would save me. The tendency to leap into situation without much preparation has lasted a lifetime, for better and sometimes for worse. In the case of Jenny Lake, my father taught me to swim when I persisted in jumping off the deep end despite dire warnings of serious consequences.

We would walk back to our cabin from the beach for lunch, leaving our bathing suits on the cloth’s line across the field from the house. Our cabin area was that private and disrobing in the out of doors was a nod to some remnant of Northern European nudism that permeated our family ethic. My mother and father both loved to go skinning dipping at night with some of their best friends, and much later in life when my mother had her own small above ground swimming pool, she insisted on discouraging and sometimes in forbidding people from keeping their suites on.

In the afternoon, after a light lunch of sandwiches we would walk a hundred yards or so through the woods to a secluded, sunny opening in the pine trees where the ground was covered with a bed of pine needles, so thick it was like a luxurious mattress, and inhale the rich smell of pine pitch drying in the sun. On chilly days we stretched out in the sun. On hot summer afternoons, we scrunched back against the trunk of one of the pine trees and hugged the shade.

Mother read out loud until I fell asleep. Mother always read to us, which must account for my love of reading today. She read me to sleep for naps and at night. She read on long car trips. Sometimes, she’d read as we sat around in the evening in our cabin in Jenny Lake doing menial chores.

My German friend, Hans Kraft and his family, also had a cottage at Jenny Lake and some afternoons I would be encouraged to see him. I’m not sure how our parents communicated and set up the date. I have a vague memory of a telephone with a hand crank that reached simply around the villages along the lake. Hans and I would always meet “by the tennis plots,” spoken in the heavy German accent by my mother and I, imitating Han’s accent. Neither Hans nor I rarely came to each other’s house.

I’m not sure what we did together. I remember a large, public building made out of the same rustic materials as our cabins, smelling of sawdust and sweat. We may have played board games or cards games there. Hans collected butterflies, and I would sometimes help chase them with a large net, but I did not stay around for the killing and pinning them in glass cases lined with dark velvet. He brought them home alive in jars and put them into what he euphemistically called a “relaxing box” to kill them before mounting.

The Adirondacks

Highlights were family excursions to the sunny meadows high above the pine trees, stretching to a ridge line where huge boulders defined the sky. The fields were covered with low bushes bearing on tough, black branches small, green leaves and bright blue berries. We attacked with buckets, which filled in an amazingly short time, even though I stuffed myself with most of the first berries I picked. They were warm in the sun, and burst in your mouth with a flavor so intense it was like a revelation! These were afternoons where we were all happy, my father for once relaxed and jovial, Mimi industrious, always our most productive picker, George finally off my case, and mother beaming, everyone thinking about blueberry ice cream, blueberry pies, blueberry jam, and a round of canning over the kerosene stove.

Less lighthearted, more wrought with significance and long silences, were the dusk excursi`ons with my father in our rowboat, trolling for bass in the far reaches of the lake. Here ritual and initiation, as day turned into dark, spread a cloak of mystery. Dusk was important, because it was when the bass fed, either rising to dry flies dropped on the surface, or betrayed by elaborate lures that moved deep under water, presumably imitating tempting fish.

We walked to the dock as the sun began to sink in the sky, my father carrying the tackle box full of lures, dry and wet flies, gloves, reels of line, lead weights of various sizes from tiny pellets to big teardrops with an eye at one end, dozens of different kinds of hooks and alternate strength leaders in small cellophane packets, some with hooks and some without. We righted the rowboat on the sand and dragged it into the water. Then Pa pulled it over to the dock and we loaded up with the tackle box, light sweaters, sometimes a blanket and a canteen of water.

I sat just behind the bow seat, squarely in the middle, where my father could see me. He wielded the oars. We would row to the most remote part of the lake, where presumably the best catches lay, just beyond the inlet. The trees hung over the lake when we stowed the oars and fixed underwater lures onto the two poles. Bass were rising here and there, but my father was not a confident dry fly fisherman. We threw the lures over board and my father began to row again, ever so slowly, just enough to keep a drift in the lines. We had to remain absolutely silent, but the lake was a cacophony of sound, the croak of giant toads in the marshes, the buzz of black flies and mosquitoes and the whoosh of bats as they swooped over the darker shadows under the trees. Water lapped against the side of the boat in rhythm with the soft groan of the oarlock. After the last songbird had quieted for the night, on the ride back to the dock after nightfall, owls would hoot their mournful cries.

The mosquitoes were fearsome at dusk, attacking every uncovered surface. We used some awful smelling stuff to keep them off, but the buzzing around the ears was enough to drive you crazy even without the bites. The black flies were worse, undetectable in the dusk, smaller than the head of pin, if anybody still knows what pins are, swarms of them, with a vicious bite ten times their size. My father was a pipe smoker in those days, and he sometime lit up and huffed out clouds of tobacco smoke to keep them at bay. Black flies were mainly gone by the end of the June.

In a sense we were there on the water because of the bugs. Fish loved them. Swarming bugs put the bass in a feeding frenzy where they didn’t think too deeply about their food. Other fishermen seemed to have much greater success than we did, but then who really knew? We certainly got many more strikes than catches, which I might have taken as a life lesson, but did not at the time. A slight tug on the line, a gentle nibbling, I’d try to gauge the right time to pull back on the line and set the hook, but both my father and I missed the moment more often than not. We still came back with fish, which my father dispatched with a short hammer he kept in the toolbox.

Just before it got too dark to see, we’d head back across the lake. We hugged the shore out of the wind for bass fishing, but any wind was long down by the time Pa stowed the fishing gears and laid into the oars, creating a breeze that gave us some blessed relief from the bugs. We’d clean the bass after we docked, amidst the tree roots along the water away from the beach. It was where I played, but the fish guts were always gone by morning, the water crystal clear again, minnows darting among the roots.

My brother introduced us to even more exciting experiences in the Adirondack Wilderness. It must have been after his sophomore year at college when he convinced my parents to go on an over night backpacking trip to climb Mt. Marcy, the highest point in New York State. A college friend had taken him camping and he knew we’d love it. I don’t remember the first trip with George, but there are photos of a trip I took with Mimi and our parents. I must have been ten or eleven years old at the time. We had stopped at one of the park’s many lean-to shelters. It rained a lot in the Adirondack. They were open on one side and had a sleeping shelf at the back. The cooking fire could be in the open on clear days or under the overhang when it rained.

Mother suffered from asthma, and walking could be a struggle for her, but she loved it. We always stopped at the first creek we crossed, named by us “Amandine Creek” after the asthma medicine mother took. In those days the water was uncontaminated by giardi and the other bi-products of civilization, and we could drink directly from the creek, icy cold, crystal clear, sweet tasting water, bubbling over pebbles, running through moss, pooling behind large rocks where trout darted away when we bent to drink.

Our father must have carried most of camping gear and food. Mother certainly carried nothing. I could not have carried much. Mimi probably helped my father with camp basics. If George were there, he certainly would have carried his share. The first day was an easy walk, with gradual ups and downs, leading toward the slopes of Mt. Marcy. It was a tame wilderness, old growth forest that had never been timbered, open over much of the ground, huge decomposing tree trunks with a high canopy of trees far above.

The Civilian Conservation Corps, a Roosevelt initiative, built the trails in the Adirondacks to make the wilderness accessible and to employ local mountain folks. The trails were carefully engineered to prevent erosion and encourage water runoff. Deliberately placed stone staircases and water bars allowed hikers to climb on stone instead of digging their hiking boots into the soil. The bars directed the water away from the trail and kept it dry. You rarely had to bushwhack around muddy stretches.

I am not sure what trail we took to climb Mt Marcy, but I remember Keene Valley, which is where the most popular trail begins, and Lake Tear of the Clouds, where the Hudson River begins at 4,293 feet. Vice President Theodore Roosevelt, an avid outdoorsman, came this way in 1901. Returning from the climb up Mt Marcy, he heard the news that President William McKinley had been assassinated and that he was now the new president.

Hikes through the Adirondacks in memory merge into one experience. Easy walking at lower elevations, the deep humus, decaying leaves and sphagnum moss making the ground springy to the step, the open spaces between the black spruce and tamarack inviting. The trails stayed on ridges where possible, but dipped through bogs over floating mats of moss or crossed ponds and large streams where the CCC had built wooden bridges. We caught glimpses of beaver in the ponds. The gnawed tree trunks they left behind were everywhere. The park had black bear (we hung our food from trees when we went on day hikes), moose, foxes, puma, but I never saw any of them. We saw porcupine, white striped skunk and white tailed deer

As we climbed higher white pines were more common and magical paper white birches appeared on the drier hillsides. I could peel the outer layer of bark to make tiny boats that I launched down rocky creeks. My father warned me from cutting the bark all the way around a tree, which would be sure to kill it.

When we gathered wood in the evening for our cooking fire, we’d be delighted to find dead birch trees, because its wood gave off colorful flames when it burned. There were also sugar maples and beech trees, red spruce, white pine, white ash, eastern hemlock, black cherry and red maple. I had no idea of their names when I was young, but the rich diversity of the Adirondack forests was remarkable. I did most of my camping later in life, in the Sierra Nevada Mountains of California. Spectacular in their own way, none had the immense variety of the eastern forests, with their nurturing sense of abundance.

Higher still, vegetation on the ground grew dense, with witchhobble, a wondrous name for a six to eight foot shrub with white flowers in the spring and red berries through the summer that attracted birds but tasted bitter when I tried them. Poison, my mother told me. I sucked tiny dollops of sweet syrup from the center of honeysuckle flowers.

One of the most spectacular sections of trail passed along the side of a sheer granite face above a lake, with small waterfalls cascading down. We climbed over rocks, scampered through tunnels under the rock and walked along a wooden escarpment under long, flowing beard-like plants, green and hairy, called “Old Man’s Beard.”

There are alpine ecologies at the top of the Adirondack Mountains. Mother’s asthma kept her from making the last leg of the trip up Mt. Marcy. She and father stopped at a ridge and waited while we children made the final ascent. The ground was exposed and the few remaining trees dwarfed. Bare patches of decayed pine needles lay between the rocks, which were covered with mosses and lichens. It was cold at the summit, on even the hottest day of summer, the wind chilling as it whipped through our hair. Range after range of mountains and valleys spread out in all directions.

Tiny wild flowers flourished between the rocks. We picked a bouquet for mother, and descended through large boulders, jagged stones and massive, exposed roots. It seemed more precipitous going down.

This was my first wilderness, experienced at a time when large parts of the world were still unknown and seemingly impenetrable, inaccessible. A few years later Tenzing Norgay and Edmund Hilary would climb Mt. Everest and today debris litters the summit. The magic of unknown nature is gone. The Adirondacks Park was a tame wilderness, with carefully constructed trails and lean-tos, the Indians all gone, the black bear and puma in hiding. There was little real danger. But there was also the powerful sense of being closer to what life was really all about.